9 November 2023

Dialogue: A Music/Game Collaboration

Image: Madeleine Cocolas and Chris Perren

Image: Madeleine Cocolas and Chris Perren © Barnsley Photography

Dialogue is a collaboration between composer/producer duo Magic City Counterpoint and indie game designers Fuzzy Ghost. Part music release, part game, it invites audiences into a surreal digital space where the music seems to conjure the environment. Inside you can wander around, interact, or just sit still and listen as the world manifests itself through sound.

In this article I want to share some of the fascinating moments and ideas that led to this work. We touch on how a violent act of deletion became the bedrock for a productive collaboration, what a music industry driven by algorithms means for creators, why collaborating across disciplines can give fresh insight into our own craft, and how to carve out space to slow down.

Magic City Counterpoint: Origins

Over the past few years I've been engaged in an unusual but extremely fruitful collaboration with fellow composer/producer Madeleine Cocolas. Madeleine and I, both composer/producers trying to carve out a practice within the constraints of parenting small children, began to collaborate on music by passing files back and forth. While this kind of remote collaboration wasn't new to either of us, there was a critical moment at the beginning of this process that made this partnership unique. We both often laugh about it now, but to my mind it was the true birth of Magic City Counterpoint. The first file I sent Madeleine was a nice little tune, not too detailed or fleshed out, ready for some extension and elaboration. Madeleine sent back - not really an extension or adaptation - but a total mulching of the original into unrecognisable sonic pulp, on top of which Madeleine had pretty much written a new song. And it was way better.

Back in my twenties, this might have upset me. However, in my late thirties, I found it freeing. Preciousness, ego, and fixations on creative control frequently get in the way of good collaborations, and in this single first response, it felt as if those things were immediately placed out of bounds. In returning the file, I felt no sense of duty to keep anything I didn't think was excellent - the music was in charge. Following that exchange, we sort of formalised those rules - no hesitation, no discussion, and no sending anything that you're not comfortable seeing completely mangled or brutally deleted.

Madeleine reflects on how "whenever you had possession of the file, you had the ability to change whatever you wanted, no questions asked! So it was a perfect mix of being able to work on something yourself at your own pace, but also then passing over to someone who you really trust and seeing what they come up with." This is how the music of Dialogue emerged. And somehow we'd made something that surprised us both - there was a special sound world here that was more than the sum of our respective styles.

Defying the Great Algorithmic Indifference

We both felt strongly about this music, and wanted to share Dialogue with the world. But time in the industry had taught us both how easily a release can just evaporate. Every day, musicians take their beloved, painstaking creations and toss them hopefully into the void, and without the right mix of money, connections, and favourable manipulation of algorithms, it sits largely unheard - like beautiful sculptures in the middle of a desert. Spotify ingests 60,000 new songs every day, and apparently 20% of the songs on its platform have never been played (an old stat, but one that I expect has only grown since). And even that which is heard, may not be really listened to; one of Madeleine's hilariously told anecdotes comes to mind, about her mixed feelings when one of her tracks found success on an Apple Music playlist called "Power Nap".

Music release strategies increasingly rely on playlisting and algorithmic recommendations. Streaming platforms take a musical artwork with history, social context, and intention, and transform it into content. Sociologist Lee Marshall has pointed out how "ideas about… performers or localities used to be important in shaping responses to particular pieces of music, the rise of playlists strips away much of that contextual information." Writer and critic Liz Pelly points out how this affects the music's perceived value, asking "can true appreciation happen on platforms that deprioritize context?" We felt our EP demanded a kind of connected, attentive listening experience that the current platforms are not geared to facilitate.

We wanted to find a way to ensure this music we loved didn't simply evaporate, and to encourage people to slow down and take it in. Madeleine shares her thoughts:

When we were workshopping ideas for releasing our EP with a visual component and started thinking about including an interactive aspect it was even more interesting to me because it's another level of engagement that people can have to the music and the experience as a whole. Once you release music into the world, you cannot control how people are going to experience it. Ideally people would sit down, carve out a space with headphones sit back and take a deep dive into it, but often it's going to be played in the background, and that's totally fine of course. Part of the beauty of having an interactive release like this is that you can make a suggestion that people do take a bit of a deep dive into the music by interacting with it and with the experience as a whole which hopefully leads to a deeper connection with the material.

I recall buying physical albums before the days of streaming, and I would often hold a sort of ceremonial first listen. Poring over the album artwork and liner notes as I listened through the entirety of the album, I immersed myself in the world of the music for its duration. I compare that to the way I often first encounter music these days, in some cases wafting by from the guts of a context-thin Spotify playlist. Dialogue aimed to facilitate something more like the former experience, within the technological reality of the present day.

Creating a Weird World Together

Dialogue felt like its own little world, and we started talking about how we could get others to step into that world for a while. Becoming high-rotation sonic wallpaper on some "Chill Moods" playlist is awesome, but for us, we would really prefer a handful of truly immersed and focused listeners than a thousand half-ignored streams.

At the same time as having these conversations, we had also begun contributing tracks to indie game developer duo, Fuzzy Ghost. Pete Foley and Scott Ford are old friends of mine, and Pete and I have a long history of collaborating, having worked on about a dozen projects together in the last 20 years. Fuzzy Ghost were the obvious choice of collaborators to help us focus our nebulous ideas and make them some kind of reality. Fortunate enough to secure Arts Queensland funding for the project, we brought Fuzzy Ghost on board. They brought the most wonderful combination of practical knowledge and wild imagination to the project, and slowly the world of Dialogue began to develop.

Pete and Scott perceived our music from a fresh angle. They really listened very closely and got right inside the work, and it was fascinating to us to discuss what they heard. Often, what stood out to them in the music was different to what stood out to us, so in collaborating with them, we were able to get new perspectives on our own creation. In digital music creation we are often working in a highly visual medium, in this case the DAW software Ableton Live, and it's hard for this not to colour or perhaps dull our visual imagination of what images the music can conjure. This cross-disciplinary process opened our ears and minds to possibilities of visual and conceptual associations that we could never have conceived ourselves.

Likewise, our collaborators found new freedoms in this project. As music creators, especially within art music and experimental genres, we are in a strangely liberated position where we are not required to provide a cohesive narrative or any kind of clear representation of life. Of course music has its own demands of cohesion and clarity of a more abstract kind, but compared to games with characters and settings and storylines, composers are generally afforded the freedom to generate, juxtapose, and play with ideas without a duty towards making sense in any symbolic way. Fuzzy Ghost, whose games feature deep and personal narratives, also found themselves with a freedom akin to the music composer. We embraced the incorporation of assets and imagery from their other games, and encouraged the inclusion of ideas from many directions, including our local visual environment in Meanjin/Brisbane.

Fuzzy Ghost reflected on this fresh viewpoint afforded by interdisciplinary work, saying "it was great to collaborate with people who don't make games themselves. We can get a bit caught up in what a game "should be" sometimes, so it was a wonderful reminder to just stop and ask, well why are they like that? What else could they be?"

Slowing Down

The four of us share a common interest in slowing down, with Fuzzy Ghost heavily inspired by Slow Cinema, and Madeleine and I both influenced by minimalism and ambient music. Dialogue was destined to be a fairly meditative and unhurried experience.

In a discussion of the popularity of slow cinema, film scholar Andrew Russell points toward the increasing pace of daily life as driving the hunger for slower media: "Evidently there is a desire for stillness and silence." As well as offering a slow counterpoint to our frenetic lives, stretching things out also draws us into details, and counterintuitively can make for a more active experience in the mind of the audience. This certainly resonates with many of our influences from the world of musical minimalism, whose slowly evolving and repetitive soundscapes can encourage more active listening. Fuzzy Ghost point out how external activity doesn't directly correlate with internal; "with a few nice visuals and some wonderful music you can be doing a whole lot in your mind without doing anything at all."

The World of Dialogue

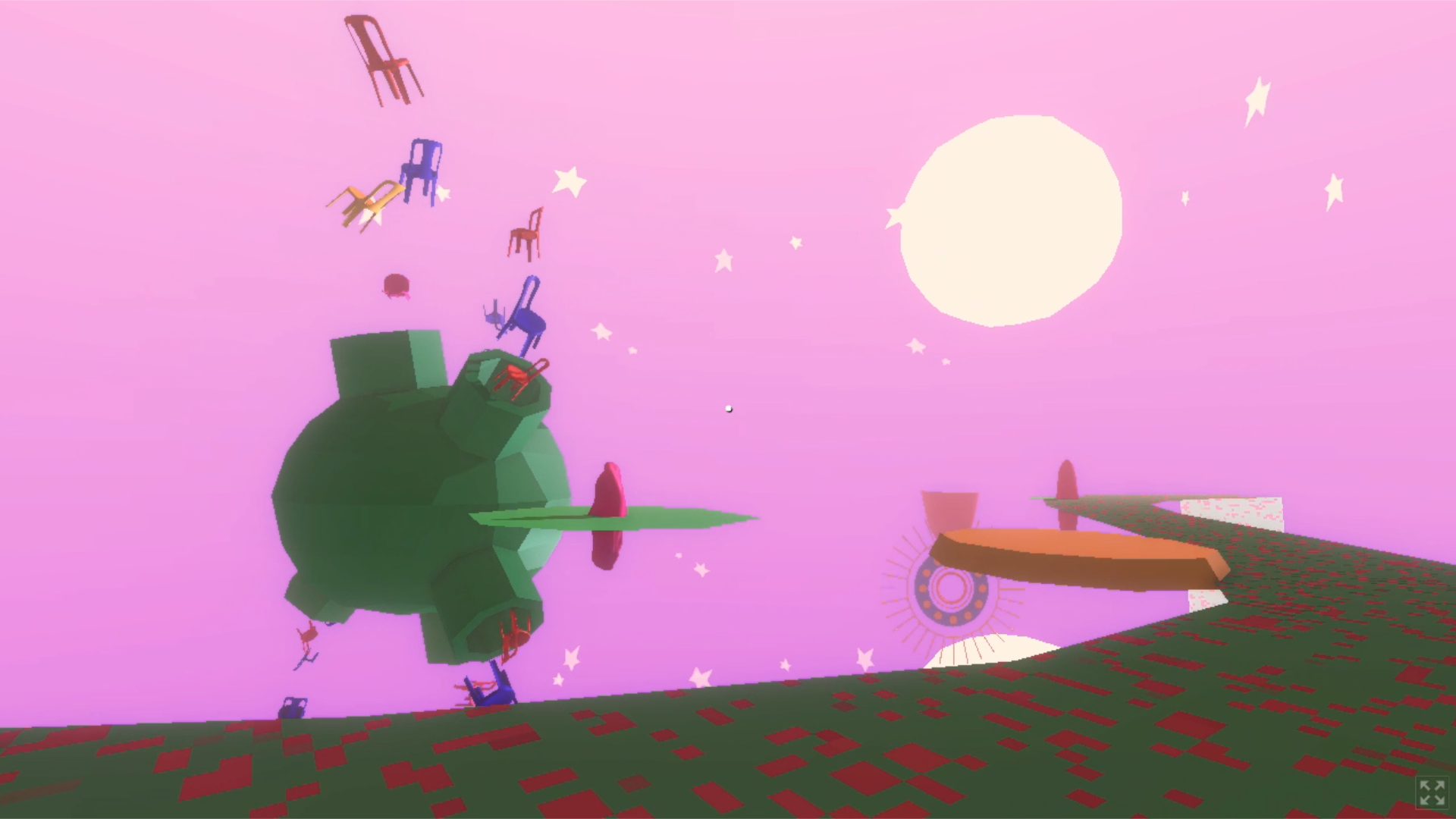

In the end, Dialogue came together as an in-browser experience, perhaps most easily likened to a game, where you enter a world which changes in subtle and dramatic ways with the music. The user is placed on a sort of island, where they can wander about, controlling the sequencing of the music through a system of arcane symbols. As the landscape changes it affords the user different possibilities for interaction - often simple and satisfying, like making trees grow, or throwing televisions at a waterfall just to watch them float down the river. Kieron Verbrugge at Press Start writes of the experience "this new island dynamically takes shape and life as you listen and wander through all five tracks. Each track brings its own distinct feeling and intent, and each is perfectly represented by the shifting hues, tones, shapes and ideas in the experience."

Many of the elements that appear speak to the context of the work, with appearances of quintessentially Meanjin/Brisbane architecture, Hills Hoists, gum trees and jacarandas, and the legendary ibis. Elements from Fuzzy Ghosts' other games appear in distorted and dream-like forms, paying homage to the origins of our collaboration. Our shared interest in slowing down and resisting unchallenged technological pace is coded into the interactions, as we hurl human artifacts into the river and conjure beautiful and strange flora to grow from the earth.

As it goes on, all of the new elements persist in the landscape, so by the end the user is surrounded by an abundance of stuff that has accumulated through their interactions. It offers a beautiful allegory to the experience of musical listening, where our memories of what we've heard so far build up as we listen, and are brought to bear on our perception of the next musical moment. The experience is rounded out in a kind of finale; as the bonus track plays, you can move about the space and say 'goodbye' to everything, sending trees, rocks, giant ibises, and Queenslander-style houses flying upwards into oblivion. For both Madeleine and I, this is our favourite part. "It's such a lovely sense of closure to the experience," reflects Madeleine.

The world that Fuzzy Ghost have manifested around our music is not overpowering or stacked with activities, but instead strikes the perfect balance of allowing space for listening, thinking, and wandering. Rather than competing with the music, it carves out a space for it and resonates along with it. For me it offers a way of listening which places the music in the centre and gives it due attention. It affords the kind of listening experience that I would like to have more of myself. It asks a lot of the listener: time, attention, and a kind of trust. But I think the rewards are great, and I hope that our humble experiment with Dialogue encourages more artists to carve out a quiet space for us to be bathed deeply in their music for just a little while.

To explore Dialogue for yourself, you need a computer with a browser (ideally Chrome), some headphones or speakers, and this link: https://magiccitycounterpoint.com/dialogue

Dialogue was supported by Arts Queensland, and featured in Powerhouse Late: Gaming and SXSW Sydney

© Australian Music Centre (2023) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

Chris Perren is an Australian composer and video artist. With creative outputs ranging from live electronics to chamber music, audiovisual artworks to match-rock, his interests lie in the spaces between genre, the collision points of sound and vision, and the complexity that can emerge from simple rules and patterns.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.