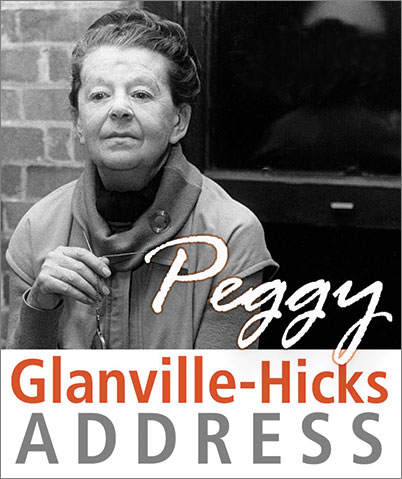

Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2018

Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address is an annual forum for ideas relating to the creation and performance of Australian music. Named after the Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, it has been igniting debate and highlighting crucial issues since its establishment in 1999.

Composer and academic Cat Hope delivered the 2018 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address in three Australian cities (Adelaide, Melbourne and Perth) on 26-28 November 2018, calling for, and drafting some steps towards, an action plan for gender equality and empowerment in our music industry. In her speech, Hope drew on recent research by her own working group (with Dawn Bennett, Sally Macarthur, Sophie Hennekam and Talisha Goh), as well as data from recent studies focusing on Australian film and popular music, to show how women are currently challenged in the music industry in terms of their income, inclusion, decision-making, mentoring, education, and the nature of their workplace. She also noted that discussions focusing on men and women should gradually start to take the form of a more general debate, including non-gender conforming people. You can read a summary of the speech on Resonate - the full transcript can be found further down.

The address concluded with the premiere of a new work Silenced, commissioned by Hope for the occasion and collectively composed by Hope, WA-based composer Dobromila Jaskot and Indonesian-born, Melbourne-based vocalist Karina Utomo.

The 2018 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address was presented through the generous support of New Music Network's presenting partners: the Elder Conservatorium of Music (The University of Adelaide), the Melbourne Recital Centre, and Tura New Music.

Cat Hope: All Music for Everyone: Working Towards Gender Equality and Empowerment in Australian Music Culture

I am very honoured to be giving the 2018 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address. Established by the New Music Network in 1999, I follow in the footsteps of amazing musicians and speakers that have included Genevieve Lacey, Warren Burt, Michael Kieran Harvey, Nicole Canham, Simone Young, and the late Richard Gill. In 2014, I was fortunate enough to be awarded the annual composers’ residency at the Peggy Glanville-Hicks House, a residence she bequeathed to the nation for use by its composers. I wonder what she would make of the state of affairs for women composers and critics now, compared to her time. She famously quipped that 'everything I’ve ever wanted to do would have been much easier had I been a boy. But never mind, I never paid much attention to it, I just marched in and there I was' (Ford, 2012). As Victoria Rogers points out in her study of Glanville-Hicks’s music, Peggy fought her own battles for equality and acceptance, and they came at some personal cost, coming as she did before the second wave of feminism (Rogers, 2017, p.107).

A 2012 article on Glanville-Hicks’s music by Andrew Ford claims she would have ‘bridled’ against the word feminist (Ford, 2012). Another person made a comment on social media in the lead-up to this address that Glanville-Hicks wouldn’t have liked the political nature of this presentation. These are not uncommon reactions to the topic of gender equality, and indeed to feminism – the concept Margaret Atwood calls ‘the radical idea that women are people’ (Caro, 2018a). I believe there are plenty of explanations for a resistance to identify with feminism – that might include considering feminism an ‘extremist’ concept, or that many young women are yet to realise that some things that happen to them could be the result of misogyny, and so blame themselves. Or that much of their income will go eventually go to childcare if they decide to have children, or that by the time these children grow up they may be categorised as ‘too old’ in their careers, and that the caring duties of the young, old, and unwell will fall to them (Caro, 2018b). It takes courage to see beyond our own experience: both looking forwards, backwards and at our lives today.

Gender is a hot topic in Australia right now. Issues such as domestic violence, the gender pay gap, the outcomes unfurling from #metoo, housing prices, and even the US elections have brought about considerable debates where the impact on women is highlighted. This year, Australia was ranked 35th (of 144) on the World Economic Forum’s global index measuring gender equality, slipping from a high point of 15th in 2006. Women are those most effected by homelessness – mostly driven there by domestic violence – abortion is still criminalised in New South Wales (and only decriminalised in Queensland this year), the gender pay gap for full time women employees is just over 22%, meaning men earn almost $27,000 each more than women each year, and they will have on average more than twice as much superannuation than women on their retirement. These figures and their relative stability point to the issue that women’s claims and contributions to work, life, and liberty are not being taken seriously. We have deep, systemic problems with women’s rights in Australia, and music is no exception. I will be showing you evidence of how women are challenged in the music industry at almost every turn – in terms of their income, inclusion, decision making, mentoring, education, and the very nature of their workplace. I will tell you how I personally stumbled on this realisation, and suggest some direct actions for change.

I would like to point out I have no training in gender theory or sociology, and I didn’t really plan to be a women’s advocate. This presentation is coming from my lived perspective as a practicing artist. I was the first person in my family to go to university, where I studied music performance, that included the occasional composition class with Roger Smalley, and have been a working as a musician ever since. My composition career began first as a songwriter in 1990, winding through bands then into improvisation, electronic and noise music, then notated art music from around 2008. I began my academic career in 2004 when my second child was three weeks old and my partner offered to take on caring and household duties. The point of this background is that I had never felt that things were more difficult for me because I was a woman. In some fields, such as noise music, I wondered if people actually sought me out for that reason. I believed that my generation was the one that had benefited from the work of feminist women before me, having forged the path I was treading.

But that was before the first female Australian Prime Minister began her work. I observed Julia Gillard’s term with disbelief. The way Gillard was talked to and talked about shocked me, but I was also shocked at how people got away with it in the public arena, because I – like many women – understood women’s rights to be human rights. Like Glanville-Hicks, Julia Gillard was just trying to get on with it. I started to look at my own world, and music, with a different perspective. I noted that some opportunities I had missed out on may have been for reasons other than that I wasn’t good enough, which is what I would tell myself at the time. I looked at the things I was making – the music I curated in my new music ensemble Decibel’s concerts, the make-up of my collaborations and so on, and reassessed how I would work in future. I curated an all women program – 'After Julia' – in 2014, thematically driven by women composers' responses to the Gillard years. I was surprised at some of the commentary about an all women program being ‘old fashioned’ and even ‘reverse sexism’, a term I hadn’t heard before then. This indicated to me that the path hadn’t been forged after all, or maybe, it was still too early to walk it.

We all have the right to be respected and treated fairly – regardless of gender, profession, race, or age. It is worth noting that Australia is the only democracy in the world without a constitutionally entrenched charter or bill of rights. This makes our judiciary almost powerless in the face of laws made in parliament. Professor Gillian Triggs, the President of the Human Rights Commission for five years, uses the example of the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act to enable the Coalition Government’s Northern Territory Intervention in 2008 as a demonstration of how executive power can be abused (Triggs, 2018). It follows that a similar situation could occur with the Sexual Discrimination Act. This lack of a bill or charter of rights also means we have no clear tool to enact our international obligations stemming from the seven international human rights treaties Australia is signatory to. These include provision for women.

Ann Summers, the author of the 1975 classic Damned Whores and God’s Police, created a women’s Manifesto on International Women’s Day last year, outlining a vision for women in Australia. It includes immediate, practical reforms to be in place by 2022, based on four basic principles of women’s equality: financial self-sufficiency, reproductive freedom, freedom from violence, and the right to participate fully and equally in all areas of public life (Summers, 2017). The focus of my Address will be on the last of these principles, full and equal participation in the music industry and the education that leads us to that. I think Summer’s principles fold together – full participation leads to financial self-sufficiency and feeds into the other principles in Summers’ Manifesto.

Full participation applies to many aspects of our lives, including cultural activity. As Scott Rankin points out in his recent Platform Paper Cultural Justice and the Right to Thrive, cultural rights are also human rights – for everyone, not just one group or another. All people – regardless of gender, socio-economic status, or cultural background, have the right to participate in the cultural life music makes a central role in. He highlights the protective power of this participation, and how cultural inclusion is about safety and social benefit. Full participation in the arts is empowering, as it enables all people to be the producers, rather than consumers, of meaning. So it follows that women’s participation in cultural activity is empowering, and benefits us all.

I will draw on two reports commissioned last year on gender equality – an APRA AMCOS study undertaken by RMIT University entitled Australian Women Screen Composers: Career Barriers and Pathways, and a Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) commissioned report by Sydney University’s Business school entitled Skipping A Beat: Assessing the State of Gender Equality in the Australian Music Industry. The executive summary of that report points out that:

'Even less recognition and power is afforded to minority groups of women such as First Nations and culturally and linguistically diverse women, women with disabilities and those identifying as LGBTQI.'

This highlights the lack of diversity in the opportunities for our broader community more generally. As our concept of gender becomes more fluid, it is important that discussions around men and women enlarges into a more general debate including non-gender conforming people as often as we do different cultural and social economic groups. It is important to challenge the binary system of male and female gender classification when undertaking research around equality and opportunity, and to consult broadly. To date, little scholarly research has been conducted into the participation of non-binary people in the arts. As a result of this significant gap in the literature, I will be focusing on those who identify as women alongside those who identify as men. I think we can assume, sadly, that the figures are even more damming for non-binary people, and I hope we will soon have access to statistics and evidence around this. I also hope that the suggestions I propose can be applied beyond men and women.

The research I am citing focuses on more financially sustainable music practices – film and popular music. Aside from some work commissioned by the Australia Council on participation in the arts more generally, I found little information relevant to gender equality in Australia from outside these styles of music. There are a number of research articles but few surveys providing broad data for the Australian situation. The 2016 National Opera Review didn’t even include the words ‘woman’ or ‘women’ in it, let alone ‘gender’. A more comprehensive study into women’s activity in the music industry, across all styles and roles, is needed for the Australian context. And when looking at such broad data, complications arise: a range of factors beyond gender come into play, including the one we really struggle with in Australia – privilege.

US academic and feminist Peggy McIntosh wrote an essay in 1988 entitled White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack that brought the term ‘white privilege’ into our vocabulary. Privilege can be defined as a set of unearned benefits given to people who fit into a specific social group. In her paper, McIntosh listed 40 statements that would show what it would be like if white privilege didn’t exist, and added eight that apply more specially to being a woman. This list has been added to and modified to highlight how privilege is not just about race, but rather a series of interrelated hierarchies and power dynamics that touch on all facets of social life – race, class, sexual orientation, religion, education, age, physical ability and gender. McIntosh notes that privilege is deeply enculturated, so that most of those who have it, are oblivious to it.

As the social strata in Australia continues to polarise, with the gap between rich and poor continuing to widen (Martin & Förster, 2013), privilege becomes even more enculturated. Discussions around privilege are often difficult in Australia, where many people see Australia as the ‘Lucky Country’ where class doesn’t exist. Tim Winton calls class the other ‘C’ word – never to be mentioned in polite company (Winton, 2013).

Privilege also means that some voices are heard over others, that contributions to debate are lifted up and highlighted or pushed down and erased. One person’s freedoms end where another person’s rights begin. To obtain full representation and participation in society, everyone should be empowered to contribute to debates and public conversation. The recent debates around 18C, the section in the Racial Discrimination Act dedicated to hate speech, made it apparent that while a democratic nation like Australia is dependent on free speech, it was not available to everyone. Yassmin Abdel-Magied Tweeted on Anzac Day last year, 'lest we forget Manus, Naru, Syria, Palestine'. Would a white, CIS gendered male have received the same backlash to this provocative statement? Although freedom of speech is technically available to everyone, it is actually only permitted, or approved to be coming from, a select, privileged few. Those few rarely include women, especially not women of colour, and definitely not Muslim women.

A recent trend associated with the ‘post truth’ phenomenon is the impact of untrue statements. Once something is out in the public domain, through the voice of a powerful individual on a far-reaching media platform, that thing can become ‘true’ by default, especially if it is believable or memorable. The tragic scenario of two high-profile male orchestral conductors dismissing their female counterparts in the Guardian in 2013 there for all to see and debate, with comments made by Russian Conductor Vasily Petrenkro including 'orchestras react better when they have a man in front of them', 'a cute girl on a podium means that musicians think about other things' and '(when a man is conducting) musicians have often less sexual energy and can focus more on the music' (Higgins, 2013). Why are there not more female conductors, we ask?

Problems relating to privilege also arise in the ‘myth of meritocracy’. Australia has a particular way of aligning merit with fairness, equality, or objectivity. A merit-based system actually discriminates on the basis of how much 'merit' a person has. It is a system that assumes everyone has equal opportunity to acquire merit – and favours those who have more of it, or are perceived to have more of it (Whelan, 2013). There are barriers to acquiring this ‘merit’, including gender, and merit needs to be measured. In organisations that emphasise merit as a selection and performance appraisal tool, men were more likely to succeed (Lawton, 2000). Does that mean that men are just more meritorious than women? No – it is more likely that this is an example of unconscious bias, reinforcing stereotypes where men are seen to be more competent than women, who are more likely to be seen to be interpersonally warmer. As I will go on to show, most women, despite how well educated they are – or, how intellectually meritorious they have shown themselves to be – remain under-represented in virtually every professional sphere of music work other than teaching.

It is interesting to note that some of the earliest tests for the measure of merit have been blind auditions for orchestras. Women’s representation in new hires went from 10% to 45% at the New York Philharmonic after blind auditions were implemented (Rouse & Goldin, 1997). Closer to home, the St Kilda film festival Tropfest saw an increase from 5% to 50% of women’s inclusion after the removal of the film makers’ identifying details in preliminary selection rounds (Ball, 2017). These examples clearly demonstrate the impact of unconscious bias on opportunities for women.

Unconscious bias, gender stereotyping, and systemic privilege exist in the Australian workforce. The popular and film music industries have acknowledged these issues, having commissioned reports seeking better data to inform actions with the aim to improve opportunities for women in our industry. But classical and jazz music are yet to act.

I have spent some time wondering if gender equity issues exist at the same level in community music making as they do ‘in the industry’. Again, we have a gap in the data. But the focus on industry driven by money. And going back to Anne Summers’ manifesto, the need for women’s financial self-sufficiency is important and as such I will focus the industry context.

APRA AMCOS membership data shows that around 20% of their members identify as female. Following on from this, the percentage of royalty payments the organisation has made to female members has fluctuated between 15% and 21% between 2007 and 2016. (Strong & Cannizzo, 2017). APRA AMCOS has reacted quickly to the report they commissioned, by setting a goal to increase their female membership by 25% over three years (APRA AMCOS, 2017). With a starting point of 20%, that’s an aim to reach 28% – not much of an increase. Other organisations, including ABC Classic FM and the Australian Music Centre, have upheld a grassroots approach to gender parity for some time, taking active measures to include women in their programming and membership respectively. This has included seeking out more women and making a focused attempt to ensure a gender balance in their activities. However, the impact of APRA AMCOS’s actions has a different significance, as their core business is royalty collection, and they have the capacity to increase the amount of revenue women earn from recordings, airplay, streaming, and live performances.

But this income is difficult to obtain. In 2017, only 28% of the 100 most played songs on commercial radio were a female act or an act with a female lead (McCormack, 2018). Streaming service Spotify reported that 21 of their top 100 artists are female, with none in the top 10 (Cooper, Coles & Hanna-Osborne, 2017 p.6). We can assume the Skipping a Beat study was commissioned for the benefit of Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance members. The report shows that the gender pay gap is acute in the creative arts, finding that the disparity in earnings had changed little from 2003 when the Australia Council found that men’s median income was 106% higher than women’s. (Cooper, Coles & Hanna-Osborne, p.6).

Data gathered by international organisation Female Pressure show us that women do not feature significantly in electronic music festival line-ups internationally, with the percentage of female acts never reaching over 10% of names on the festival, if at all. Two of the largest Australian music festivals showed significant gender imbalances: the 2017 versions of Splendour in the Grass had 74% male-only acts and Groovin The Moo had 79% male-only acts (McCormack, 2017). Camp Cope called out the lack of female headline acts in the Falls Festival last year in the lyrics of their songs and on social media. Two other prominent festivals, Days Like This and Spilt Milk, had no female acts whatsoever in 2016. Spilt Milk did, however, take the criticism on board and changed its practices somewhat the following year. They were singled out at a roundtable on the issue of women in music, conducted by Music NSW, demonstrating the effectiveness of direct lobbying, but also the need for education around these issues and their importance.

The Australia Council found that 32% of all musicians working in Australia are women, and 27% of all composers working in Australia are women (Throsby & Zednik, 2010). Yet concert programs don’t even reflect this rather depressing imbalance; they are overwhelmingly dominated by men. This is not a perception, but a fact – music written by women is not featured widely in performances of any musical genre. In 2013, only 11% of the works in Australian new art music concerts advertised online featured works by women, for example (Macathur, 2013).

Despite this evidence, there is a recurring lack of acknowledgment that difficulties exist for women in the music industry. This can come from both men and women. As was the case for me, an individual’s personal experience can inform their view. For others, it can be a simple lack of interest or inability to see the relevance. Occasionally, members of the music community lash out with comments such as ‘if you are good enough, you’ll get by’ (actual comment from senior female sound artist) or ‘it’s hard for everyone, not just women’ (senior male jazz artist). But the data is telling us that this is simply not the case.

In screen composition, women were twice as likely than men to believe that their gender had a negative effect on their careers: that they took longer to become established, found it harder to get jobs and were discriminated against – telling us that men perceived the industry as being much less gender-biased than women do (Strong & Cannizzo, vi, 2017). Men are either unaware or call it something else – for example, 36% of male respondents disagreed with the statement 'Sexual harassment is common in the industry' and 36% of women agreed (ibid); it is likely that what men and women consider sexual harassment is understood differently according to their gender.

Similar issues around perception exist in the education space. An informal review by a national student-led group supporting women in jazz, All In, found lecturers often disagreed that establishing a career in jazz was more difficult for women. This perception exists despite an overwhelming percentage of jazz instrumentalists being men, with recent research in the UK showing that less than 5% of jazz instrumentalists are women (Barrett, in Schriver, 2018). This is compounded by the issue that many tertiary music schools have few women – sometimes none – in their permanent faculty, reinforcing an expectation that students will not find other women in the workplace they aspire to.

Men’s fellowship can be found at the very highest level of industry representation. It has been noted that there are more people are called Peter, David or John than there are women on boards in Australia (Whalquist, 2015). The fact that CIS gendered, white, able-bodied men aged 40-69 years make up only 8.4 per cent of the population but represent the majority of Australian board leadership makes this statistic even more alarming (Liveris in Liddy & Hanrahan, 2017). Likewise, ABC’s Radio’s Hack project found that only 35% of board members on peak music bodies are women (McCormack, 2017). While these figures are actually reasonably healthy compared to other fields of work, they do not accurately reflect the state of play ‘on the ground’, where women are working in many different facets of the industry. Women are well represented in junior roles in key music industry bodies at 58% but hold only 28% of senior and strategic roles. Of 120 independent Australian Record labels registered with AIR, 80% of record managers are male (McCormack, 2016) and the ARIAS and AIR currently have no female board members (Cooper, Coles & Hanna-Osborne, 9). It seems clear from this data that men dominate the major decision-making structures of the popular music industry, and this in turn has an impact on the way decisions are formed and delivered.

Together with my colleagues Dawn Bennett, Sally McCarthur, Sophie Hennekam, and Talisha Goh, I have been undertaking research into the experience of women composers around the world. We found that many female composers perceived a lack of support from other women, with most not being able to identify a mentor in their early career (Bennet et al., 2018) – as was the case for me. Many even hide their gender when applying for opportunities (ibid.), and most wanted more mentoring than they had access to (Music Victoria, p.6). But the study also revealed many women are finding a different kind of mentorship online, with 70% stating that they had found a large degree of support through social media groups such as ‘Women in Composition’ on Facebook (Bennett et al., 2018).

In fact, research demonstrates that men are more likely to mentor other men rather than women, as they see a younger version of themselves in their younger male counterparts (McSweeny, 2013). This suggests that if more women were in senior roles, they would be more likely to mentor women their junior. There is also an expectation that women will automatically support other women, but this may not happen for a range of reasons – some feel that their gender has not hampered their career so see no need for it, some do not want to think about how their gender may have affected their career. Then there are those who never had support themselves dealing with the challenges they faced in their career and carry a degree of bitterness around that. Then there are some who enjoy having been, or still being, the 'only woman in the room'. Another assumption is that women know about what other women are doing or aspire to. Given that most women are surrounded by men, as evidenced by the statistics I shared earlier, women’s work is not always visible. And further, the labour of looking for women to make ‘balanced’ programs is then shifted back onto the women themselves, compounding the problem even more.

Another issue raised in research was that of confidence (Bennett et al., 2018). This is hardly surprising when there are few role models, few women featured in the educational canon, and few women on concert programs and radio playlists. It brings attention to an important issue – the perception held by some fellow artists that if one women can make it, all women should be able to succeed. This then goes on to create the subsequent impression that if other women do not succeed, it is due to personal failings rather than anything systemic. This has the result of further demoralising individuals, especially those new to the industry in the rather vulnerable position of ‘proving themselves.’

Approximately 50% of all music students in Australia are women (McCormack, 2018). However, the canon most music students are taught features little, if any, compositions, software, arrangements, or songs made by women. Performances of works by female composers are also likely to be rare in student recitals and staff performances. It also follows that if music schools are not educating all their students about women’s works, the students are unlikely to expect or seek any when they graduate and enter the profession. Is this absence from the curriculum because there are no women in music through time? No. I think most people would agree that it is important in our current educational climate, where students are paying increasingly more for their education in public universities, that music students are provided with the tools to work in a professional career. Australian funding for education is much less than the OECD average, meaning individuals and families are paying instead (O’Connell, 2017). It is important that they learn about the benefits of diversity and the different kinds of voices that exist in a field of practice. This can be evidenced in what they study, what they perform, and who teaches them. A canon of music where they can see their gender represented is important to their confidence moving forward, and central to the normalisation of gender diversity. It is the responsibility of those working in educational institutions to establish and teach a canon that is relevant to the careers of musicians of our time, and not default to what they were taught or who they happen to know.

Studies of music education in primary and secondary schooling suggest that the socialisation of future musicians into gendered music practices begins early on in life and develops alongside children’s social identities. (Roulston and Misawa, 2011 in Strong & Cannizzo, p.52). Research has shown that some musicians – many of them teachers – believe certain instruments and careers are more suited to men than women. Drums, trombone, and trumpet are seen as ‘masculine’, the flute, clarinet, and violin as ‘feminine’ (Green, 2002, p.140). Jazz is a genre that commonly features the aforementioned ‘masculine’ instruments, and this could help explain why women’s participation is low. Research indicates that primary and secondary schools perpetuate subtle definitions of femininity and masculinity as connotations of different musical practices and music styles, in which pupils invest their desires to conform (ibid., p.142), a trait that tends to play out in jazz in particular. Many women working in jazz say they feel they need to be better than their male counterparts to simply access similar gig opportunities.

So, if around 30% of musicians working in Australia are women, what happened to the other 20% of students studying music in our educational institutions? Some may of course go into other careers and many musicians don’t undertake formal music education. But given that many music students will not ‘see’ themselves in a future career, not in the music they study, in who teaches them, or in concert programs out in the ‘real world’, they are already a step behind their male counterparts.

The music workplace varies considerably between genres. A sticky carpeted pub is quite different to a concert hall, a jazz club is different to a performance at a wedding ceremony or stadium. But sadly, sexual assault and harassment of women is an ongoing issue in popular and jazz music communities, with incidents at major rock music festivals common (Cooper, Coles & Hanna-Osborne, 2017, p.7). A survey in Melbourne showed just over 80% of people at gigs believed that unwanted sexual attention was common in licensed venues, and an even higher number saying they had seen it take place (Fileborn, 2012). I would expect results to be similar in other states of Australia.

These issues create difficulty for the informal way most networking is undertaken. In many music genres, future opportunities are found and created at the post show ‘hang’ (Strong & Cannizzo, 2017, p.17). It is not surprising women would not wish to network at a music venue after a gig. This is compounded by statistics that show us 90% of women use informal networking as the lead strategy for career development (Music Victoria, p.7). It seems that, like the mentoring I mentioned earlier, women are finding online networking a more rewarding, fruitful, and quite frankly – safe – way to make contacts and seek opportunities. Further, the gendered nature of caring responsibilities sees many women drop out of the industry to raise children, with many believing that raising a family while undertaking a career in the music industry was incompatible (Music Victoria, 2015, p.4). The casualisation of work in the music industry mixed with lower pay impacts women strongly in financial terms, especially those who are primary care givers in families.

It is hard to be optimistic in the face of this data, but I believe there are already changes unfolding. The problem is systemic at the highest levels of the industry; boards, education and politics. As such, some of the most promising activity is coming from younger, emergent artists and academics, who are making decisions to ensure that they curate, organise, teach, and research in a way that is careful and considerate. Being willing to discuss the issues openly, or even just include women’s music in any discussion, is an important part of the possibility for change. This is steady and focused work where consultation is broad and ideas are considered with a new frame of inclusion and openness. It is not bred from the master and apprentice model, it comes from a truly global, internet family that deserves financial and moral support. This new wave of young agitators is a group that sees privilege for what it is, calls out discrimination when they see it, activates bystanders, supports those of like mind, challenges conventional authority and reads theory differently. These are people for whom the new world of work is not a challenge, but a reality. They are not fighting over scraps – the last CDs, royalties for downloads, the last magazine run, a sales window. They make their opportunities and invent the paths. It doesn’t always work, but the importance is in the attempt.

There are many individuals and initiatives working for change, too many for the scope of this occasion, but here are some I am aware of. In the art music sphere, Making Waves, co-directed by Peggy Polias from Sydney and Lisa Cheney from Melbourne is a website that features podcasts focused on Australian composers from around the country, with a 50/50 gender spilt. Perth’s Tone List, a music label for exploratory music, is outwardly collaborative and inclusive, organising concerts, interviews, and workshops of different kinds, and feeding into larger organisations in that state. The aforementioned All In is promoting women in jazz music through positive reinforcement, support and community. Frontyard Projects in Sydney is a community-driven multi-arts centre looking at sustainable practices in the arts. Listen, a collective based in Melbourne, is a using a feminist perspective to advocate for different points of view, focusing on people that consider themselves marginalised within Australian music. Nat Grant’s ‘Prima Donna Podcast’ is a project where Grant intertwines interviews with senior female artists with her own compositions, formulating a new approach to oral histories. Cut Common, founded and edited by Tasmanian Stephanie Eslake, offers a new and fresh alternative to classical music journalism, with a focus on inclusivity. New label and platform ‘Women of Music Production Perth’ (WOMPP), founded by Rosie Taylor and Elise Ritz last year, is now a community of over sixty people teaching confidence building, social awareness, and a supportive base for those seeking a public platform, including trans and non-binary artists.

But change is not only coming from the younger generation of artists. In response to the low number of women in the ARIA awards, a new awards night took place in Brisbane this year the Australian Women in Music Awards, with Artistic Director Katie Noonan announcing that the awards should be read as, and I quote 'a powerful signal to our industry, our artists and our audiences that female musicians can, should and will take centre stage'. Rather than fight for a place in the ARIAs, a group of women have decided to make their own, more inclusive awards that acknowledge First Nations and multicultural performers and humanitarian work. Other award nights are demanding gender balance on selection panels.

Education programs are an important part of creating opportunities – such as the Sydney Conservatorium’s ‘composing women’ program, and the Summers Night Mentoring Project I established with Adelaide pianist Gabriella Smart. These aim to provide opportunities for women irrespective of age or musical style to be mentored by a combination of male and female performers and composers, through in workshops, concert opportunities and touring programs.

Books are still important – they shape the canon, and perpetuate information about our culture through time. It remains more important than ever that they are developed by rigorous researchers who understand the nature of oral history, are consultative and fact check. This was recently brought into sharp relief with the publication, and soon after shredding, of Clinton Walker’s book Deadly Women’s Blues published by NewSouth in February this year and withdrawn from sale for pulping the following month (Corn & Langton, 2018). After many of the women in the book complained to the publisher that they had not been consulted and were inappropriately, or plain ‘incorrectly’ represented in the book, the publishers relented and withdraw the book. Peggy Glanville-Hicks was not so fortunate. The first full-length biography of her life by her friend Wendy Beckett, published two years after her death, was riddled with factual errors and misunderstandings of the nature and practice of music (Robinson, 1999, p.95).

But books are no longer the only medium for interrogating practice. The increasing popularity of practice-led postgraduate degrees in music is opening up a different kind of peer reviewed avenue for artist’s perspectives. Since practice led higher degrees were introduced in Australia in 2005 (Green, 2007), the exegetical documents created in these research projects are an important and valuable source of contextual information around process and intent for all artists, and a new, self-regulated avenue for women. These documents are different to the traditional musicological approach, creating historic documents in the voice of the artists themselves. These degrees are also providing an additional income stream for some artists, through three-year federal government scholarships.

Given that music forms part of the daily routines of most Australians at work and during their leisure time – research showing us that more people listen to music than exercise – issues of how society is represented in our music culture are important. Full participation in this cornerstone of our culture is essential if we truly uphold a society of equal opportunity and inclusivity. The power of cultural participation demands to be shared by all. This participation can be driven by women themselves, but also requires men in positions of influence to insist on change. As Clementine Ford says,

'Equality comes from people either sacrificing their privilege or having it forcibly taken away from them. It does not come from waiting for the oppressed to rise up and meet it.'

Some of us do have the ability and circumstances to rise up and meet challenges. Some organisations are thinking, trialling, and implementing different methods to make change – formal quotas with the aim of ‘shocking’ the system into a new frame, ‘mindful’ programming, where people in positions of power and decision-making endeavour to just look harder and be conscious of the need for balance.

For my small part of this address, I have commissioned a collaborative composition that will premiere at conclusion the spoken part of the evening. Building on the collaborative collectives of the feminist movement, and recent projects in visual arts, I have chosen to work with another composer from a different cultural and stylistic background, and performer of a different music style to my own to create a new work together.

Artistic collaboration and collective authorship can be powerful ways to overcome some stereotypical expectations of the creator as a ‘master creator’ and the performer as a subservient to their single, more often than not, masculine, voice. This approach can also be applied to program curation, as the artist-led Melbourne organisation Aphids has done. Driven by a feminist methodology where collaboration, listening, and what they call ‘radical leadership’ is highlighted, the company has three co-directors who claim they 'want to be active in shaping an artistic and cultural landscape that gives space to multiple voices – a sense of welcome, dialogue, criticality, experimentation and support for diverse artists and audiences' (Zilla and Brook, 2018).

Australia has a rich, though under-acknowledged, history of women-only art collectives and collaborations that have created alternative pathways for the careers of visual and performance artists. They engage flexible, organic, and practical working principles that determine a collective practice, rather than pre-set ideologies, intentions or artistic outcomes (Mayhew, 2015, p.226) that could be shared by any collaborative group. We could do more of that in music.

Silenced is the title of the piece I have commissioned and co-authored with polish born, Western Australian-based composer Dobromila Jaskot and Indonesian-born, Melbourne-based vocalist Karina Utomo. It is my own experiment with the principles championed in the women’s art collectives of the 1970s but also recent groups such as The KingPins, Brown Council, Soda_Jerk, and others. Other musicians are currently working this way: Brisbane duo Clocked Out are undertaking a series of collaborations where they co-author and curate with composers, and Brisbane composer Cathy Milliken ran ‘Collective Composing’ workshops at the Darmstadt Summer Course this year.

But before we move to the music, I would like to conclude with some suggestions to enact change.

The recent reports I have cited this evening have resulted in their own recommendations. The APRA AMCOS report made six: engage men in equity initiatives, create networking and partnership opportunities, spotlight female role models, help girls to engage with music technology, and undertake ongoing research in women and music-making. (Strong & Cannizzo, 2017, p.57-59).

The Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance report, however, calls for the collection of more and better data on the music industry, establishment of a gender equality industry advocacy body, the use of gender equality criteria in deciding public funding outcomes, an increase of women in decision making structures, addressing gender bias by prioritising inclusivity and representations as core industry values. (Cooper, Coles and Hanna-Osborne, p.2)

I would endorse Julian Meyrick’s call for a position of high office for a selected artist. Meyrick frames the possibility of a Chief Artist or Cultural Practitioner as something akin to the Chief Scientist role we currently enjoy (Meyrick, 2016). I doubt ‘Chief Artist’ is the right title, but a figure head of some kind could be useful to remind us all of the importance of art and culture, and highlight the issues within the field. I took the liberty of rewording the part of the Chief Scientist's job description (my changes in bold) featured in Meyrick’s article, so that it might work for a similar role from the arts.

'… [provide] high-level independent advice to the Prime Minister and other Ministers on matters relating to art and culture … to identify challenges and opportunities for Australia that can be addressed, in part, through the arts… To be a champion of artistic practice in all its forms and the role of creativity and cultural activity in the community and in government.

'Finally, the Chief Artist is a communicator of the value of art to the general public, with the aim to promote understanding of, contribution to and enjoyment of art and culture.'

These are actions for industry, organisations, and political leaders. We also need action for individuals, things that each of us undertake. One by one we can support diversity and opportunity by challenging our assumptions and calling out concert, gig, festival and radio programming, commission opportunities, and label releases when they consistently exclude or marginalise those who do not identify as men. We need to talk beyond, as well as within, our own musical networks. Organisations, and those in positions of influence need to work on the way we share information, focus our interest and ensure we provide options for people who may need to do things differently than others.

I propose three different levels of action:

The first of these is right at the top, where it seems that the most issues exist in terms of representation and indeed, willingness to include representation, at the highest levels of industry. Despite endless statistics and reports generated by the business community demonstrating the dearth of women at the most senior levels of decision making, the music industry has overall, been slow to react. Musicians need to lobby the institutions that claim to represent us, and make sure they do. Men need to stand up and lobby with women, and make positions available to us.

Secondly, there are many very good projects – administrative, collective and artistic – that are started by groups of independent individuals, that then go on to partner with more established institutions. These groups need our active endorsement and assistance to ensure they have the support to retain their opening gambit of being inclusive, easily accessible and not over editorialised. The industry needs to make space for them.

Finally, there are those of us just trying things out. Curating programs, making and performing new work, championing their friends and collaborators, forming collectives, interviewing those they respect, writing about each other, creating communities as alternatives to the status quo that may have never given them an opportunity to join. These individuals and groups need our participation and respect, they need space and time to evolve and experiment, permission to take risks as well as permission to fail. Perhaps they are the most important of all.

The world of music is fascinating and complex, as are all things driven by social interaction. As highlighted by the #metoo campaign, the current level of interest in the topic is high, so now is the time to move – to ensure we go beyond pointing out the issues and on to make changes at every level where we can, whether it be to shock the system, change our language, or enter a conversation. The world of music will be better for it, for all of us.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Nat Grant, Lisa MacKinney and Karl Ockelford toward the preparation of this paper, the contributions of Dobromila Jaskot and Karina Utomo in the creation of the work Silenced, and thank the New Music Network for their support.

References

APRA AMCOS, (July, 2017) 'APRA AMCOS leads music industry toward gender parity, aims to double new female members within three years' http://apraamcos.com.au/news/2017/july/apra-amcos-leads-music-industry-toward-gender-parity-aims-to-double-new-female-members-within-three-years/

Ball, Simone (2 November, 2017) 'The TropFest Redemption: Why It Matters That Half This Year’s Finalists Are Women' https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/simone-ball/the-tropfest-redemption-why-it-matters-that-half-this-years-fi_a_21711111/

Barrett, I, in Schriver, L (2018) 'Jazz is Dominated by Men – so what?' http://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/11/jazz-is-dominated-by-men-so-what/

Beckett, W, & Hazlewood, L (1992) Peggy Glanville-Hicks. Pymble, NSW: Angus & Robertson.

Bennett, D, Macarthur, S, Goh, T, Hennekam, S, and Hope, C (2018) 'Hiding gender: How female composers manage gender identity'. Journal of Vocational Behavior.

Bennett, D, et al. (2018) 'Creating a career as a woman composer: Implications for music in higher education'. British Journal of Music Education pp. 1-17.

Browning, J (May, 2016) 'Equal Arts: Discussion Paper'. Victorian Women’s Trust, http://www.cacwa.org.au/documents/item/506

Caro, J (29 July, 2018a) 'The Book that had Redefined my Outlook on Sexism' https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/life-and-relationships/the-book-that-had-redefined-my-outlook-on-sexism-20180726-p4ztq5.html

Caro, J (29 September, 2018b) 'There comes a day When Feminism Speaks to All Women' https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/life-and-relationships/there-comes-a-day-when-feminism-speaks-to-all-women-20180926-p5066q.html

Cooper, R, Coles, A,and Hanna-Osborne, S (2017) 'Skipping a beat: Assessing the state of gender equality in the Australian music industry'. University of Sydney Business School, Sydney, N.S.W. http://sydney.edu.au/business/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/315275/Skipping-a-Beat_FINAL_210717.pdf

Corn, A, and Langton, M (2018) 'What writers and publishers must learn from the Deadly Women Blues Fiasco'. https://theconversation.com/what-writers-and-publishers-must-learn-from-the-deadly-woman-blues-fiasco-92512

Cunningham, S, and Higgs, P (2010) 'What’s your other job? A census analysis of arts employment in Australia'. Melbourne: Australia Council for the Arts.

Eikhof, D R and Warhurst, C (2013) 'The promised land? Why social inequalities are systemic in the creative industries'. Employee Relations, 35(5), pp.495-508

Fileborn, B (2012) 'Sex and the city: Exploring young women’s perceptions and experiences of unwanted sexual attention in licensed venues'. Current Issues Crim. Just. 24, p.241.

Ford, A (28 Dec, 2012) 'The Sparkle of the Miniature' https://insidestory.org.au/the-sparkle-of-the-miniature/

Grant, N: Prima Donna Podcast. https://www.primadonnapodcast.com/

Green, L (2007) 'Recognising Practice Led Research – At Last!' Hatched 07 Discussion Papers, Hatched 07 Research Symposium, Perth: Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. p.9-12

Green, Lucy (2002) 'Exposing the Gendered Discourse of Music Education'. Feminism & Psychology 12.2. p.137-144.

Goldin, C & Rouse, C (1997) Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of 'blind' auditions on female musicians. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Higgins, C. (3 September, 2013) 'Male Conductors are better for orchestras, says Vasily Petrenko'. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/sep/02/male-conductors-better-orchestras-vasily-petrenko

Larkin, M (26 Sept 2018). 'The Under-represented Many: Gender Prejudice in Music' https://overland.org.au/2018/09/gender-prejudice-in-music-and-the-under-represented-many/

Lawton, A (2000) 'The Meritocracy Myth and the Illusion of Equal Employment Opportunity'. Minn. L. Rev. 85 p.587.

Macarthur, S (2013) 'Off key: women composers get a raw deal on play rates'. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/off-key-women-composers-get-a-raw-deal-on-play-rates-17149

Macarthur, S, Bennett, D, Goh, T, Hennekam, S, and Hope, C (2017) 'The rise and fall, and the rise (again) of feminist research in music: "What goes around comes around" ’. Musicology Australia 39, no. 2, pp.73-95.

Making Waves https://makingwavesnewmusic.com/

Martin, J P, & Förster, M (2013) 'Inequality in OECD countries: the facts and policies to curb it Rising income inequality risks leaving more people behind in an ever-changing world economy' https://insights.unimelb.edu.au/vol15/pdf/Martin.pdf

McCormack, A (7 March, 2017) 'By the Numbers 2017: The Gender Gap in the Australian Music Industry'. http://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/by-the-numbers-the-gender-gap-in-the-australian-music-industry/8328952

McCormack, A (8 March, 2018) 'By the Numbers 2018: The Gender Gap in the Australian Music Industry'. https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/by-the-numbers-2018/9524084<

McIntosh, P (2010) 'White privilege and male privilege'. The teacher in American society: A critical anthology 121. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED355141.pdf?utm_campaign=Revue%20newsletter&utm_medium=Newsletter&utm_source=revue#page=43

Mayhew, L R (2015) 'Collaboration and Feminism: A Twenty-First Century Renascence'. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 15.2 pp 225-239.

McSweeny, E (April 10, 2013) 'The Power List: Why Women Aren’t Equals in New Music Leadership and Innovation'. http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/the-power-list-why-women-arent-equals-in-new-music-leadership-and-innovation/

Meryick, J (September 9, 2016) 'Why Australia Needs a Chief Artist' https://theconversation.com/why-australia-needs-a-chief-artist-64974

Music Victoria (September, 2015) 'Women in the Victorian Contemporary Music Industry' http://www.musicvictoria.com.au/assets/Women%20in%20the%20Victorian%20Contemporary%20Music%20Industry.pdf

O’Conell, M (14 September, 2017) 'Australians pay more for education that the OECD average – but is it worth it?' https://theconversation.com/australians-pay-more-for-education-than-the-oecd-average-but-is-it-worth-it-84002

Rankin, S (2015) Cultural Justice and the Right to Thrive. Platform Paper 57. Sydney: Currency House. https://www.currencyhouse.org.au/node/273

Robinson, S (1999) 'On the Auto/Biography of Peggy Glanville-Hicks: Telling a Life—Or Lies?' Australasian Music Research 4. p.105.

Rogers, V (2017) The Music of Peggy Glanville-Hicks. London: Routledge.

Strong, C and Cannizzo, F (2017) Australian Women Screen Composers: Career Barriers and Pathways, RMIT, Melbourne.

Summers, A (7 March, 2017).'The Women's Mainfesto: A Blueprint for how to get Equality for Women in Australia'. http://legacy.annesummers.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Womens-Manifesto.pdf

ToneList http://www.tonelist.com.au/

Triggs, G (2018) Speaking Up. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Throsby, D, & Zednik, A (2010). Do you really expect to get paid? An economic study of professional artists in Australia. Melbourne: Australia Council for the Arts.

Whelan, J (16 October, 2013) 'The myth of merit and unconscious bias' https://theconversation.com/the-myth-of-merit-and-unconscious-bias-18876

Whalquist, C (6 March, 2015) 'Fewer women at the help of top Australian companies than men named Peter'. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/mar/06/more-men-named-peter-at-the-helm-of-asx200-companies-than-women

Winton, T (2013) ‘The C Word - Some thoughts about Class in Australia’ The Monthly, Dec 2013 - January 2014 https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2013/december/1385816400/tim-winton/c-word

World Economic Forum 'Global Gender Gap Report 2016 – Reports – World Economic Forum'. http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2016/rankings/

Zilla And Brook (19 Sept 2018) 'Aphids Appoints new Feminist Co directorship of Eugenia Lim, Mish Grigor and Lara Thoms'. http://www.zillaandbrook.com.au/aphids-appoints-new-feminist-co-directorship-of-eugenia-lim-mish-grigor-and-lara-thoms/

About Cat Hope

Cat Hope is a composer, performer, songwriter, noise artist and researcher. She is a flautist and experimental bassist who plays as a soloist and as part of other groups. She is the director of and performer in Decibel: a group focused on Australian repertoire, the nexus of electronic and acoustic instruments and animated score realisations, which led to her being awarded the the APRA & AMC Award for Excellence in Experimental Music in 2011 and 2014. She has been a resident at the Peggy Glanville Hicks composers house, as well as a Civitella Ranieri, Visby International Centre for Composers and Churchill Fellow.

Hope's work has been discussed in books such as Loading the Silence (Kouvaris, 2013), Women of Note (Appleby, 2012), Sounding Postmodernism (Bennett, 2011) as well as periodicals such as The Wire, Limelight, Neue Zeitschrift fur Musikshaft and Gramophone magazine, who called her 'one of Australia’s most exciting and individual creative voices'. Her works have been recorded for Australian, German and Austrian national radio, and her 2017 monograph CD on Swiss label Hat Hut won the German Record Critics prize. An advocate for Australian music and gender diversity, Hope is also the co-author of Digital Art – An Introduction to New Media (Bloomsbury) and Professor of Music at Monash University.

For more information visit: www.cathope.com.